This month’s topic can get mundane in a hurry. Indeed, the world of option pricing is littered with mind-numbing mathematics and sleep-inducing theory. But fear not! We’ve taught the masses for years and have created clever ways for breathing excitement into an otherwise torpid topic.

Today’s goal is simple – to help you understand just what makes calls and puts tick. Like a biologist dissecting a frog, we’re donning the gloves and manning the microscope to investigate the innards of an options contract. By better grasping how these came to be and how they behave you will be more prepared to trade them for profits.

An Automobile Tale

Once upon a time, I was a strapping young lad, flush with cash and in need of a car. Like any testosterone-driven, single 20-something, I was seeking a sweet ride that would transport me in style and make it easier to snag a mate. I settled on a pearl white Lexus IS 350 complete with a tricked out Mark Levinson sound system. Like a dum-dum I bought it brand new because, well, we’re all allowed a foolish decision or two in our twenties.

Fast forward eight years and with a wife, one-year-old, dog and baby number two on the way my beautiful car was no longer practical. It was time to upgrade to a mini-van. For the first time in my life, I entered the used car market as both a buyer (the mini-van) and a seller (the Lexus).

The principal problem I faced was my ignorance of what a fair price looked like for either automobile. If you think about it, this is an issue encountered by participants in every marketplace. My fear came in two forms. As a buyer I feared paying too much for the mini-van, getting ripped off by a shady salesman named Slick Rick. As a seller I feared receiving too little for my precious roadster.

Fortunately, fair and transparent pricing for autos was established long ago. To prepare me for my shopping adventure I surfed to Kelly Blue Book, the authority on car pricing, to discover what payment I should demand and what price I should be willing to pay for both vehicles.

See, without fair and transparent pricing markets don’t function. Buyers and sellers just aren’t willing to come together on a mass scale. That, dear readers, is the moral of the story. And, in case you were wondering, I did offload my car and got a sweet deal on a van (used this time 😊).

When Three Wizards Built a Math Model

Options trading didn’t exist as a large scale market before the 1970s for one crucial reason: the world lacked a systematic method, one both fair and transparent, for pricing options contracts. Back then there was no Kelly Blue Book for option pricing! As a result, a trader in New York may have used a completely different method than a trader in London for identifying a reasonable price for a call option. Because of this, both parties brought skepticism and hesitation to the table.

This was a problem soon to be solved by three geniuses, well versed in the magic of mathematics. Their names, to be remembered and revered by options traders the world over, are Fischer Black, Myron Scholes and Robert Merton. After toiling in their laboratory with logic and numbers, inspiration finally struck, and they created what is now known as the Black-Scholes model. With it, traders can define what a fair price for option prices is. Now, market participants all over the world can use the same variables to price an option. Buyers no longer need to fear overpaying, and sellers no longer need to fear being underpaid.

A few weeks after the model was born options trading began in earnest on the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE). Wall Street’s adoption of these derivatives has been growing ever since. And with the advent of online trading and discount brokers, it is now feasible for John Q. Public to come and partake of the bounteous advantages offered by these now fairly priced contracts.

As for our trio of Einsteins, Merton and Scholes received the 1997 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for their ground-breaking discovery. Sadly, Black had since passed making him ineligible for the prize.

How to Bake an Option

Fortunately for the layman, grasping convoluted math models isn’t a necessary pre-requisite for successful options trading. Instead, all you need to know are the ingredients of the recipe. To continue the cooking analogy, picture Black, Merton and Scholes as three chefs attempting to bake the “un-bake-able.” Like pioneers they ventured into virgin territory, intent on crafting a culinary delight that all other cooks thought impossible. For days, perhaps years, they labored, testing and trying, shaking and tasting until finally, they got it. In the end, their recipe was whittled down to six ingredients: stock price, strike price, time to expiration, volatility, dividends, and interest rates.

Commit these to memory. They have the potential to pay dividends, to bring pleasure more potent than your great grandma’s chili. Let’s take a look at each in greater detail to discover precisely how they impact the price of an option contract. And speaking of contracts, let’s set the table with a brief review of call and put definitions.

– Call Option

A call option gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy a stock at a set price on or before the expiration date. Because they lock-in the right to acquire stock, calls increase in value as the stock rises and vice versa. Buying calls is a bullish trade.

– Put Option

A put option gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to sell a stock at a set price on or before expiration. Since they lock-in the right to sell stock, puts increase in value as the stock falls and vice versa. Buying puts is a bearish trade.

Now, grab your mixing bowl and let’s talk ingredients.

– Stock Price

The price of the underlying stock that we’re creating an option on has a substantial impact on our option’s value. Are we pricing a contract on Amazon.com, Inc. (AMZN), a behemoth of a stock with a $1,600 price tag? Or, are we pricing an option on Ford Motor Company (F), a dirt-cheap stock at $11? Here’s the rule to remember: the higher the stock price, the higher the option’s cost. It’s as simple as that.

– Strike Price

The strike price is the “set price” that the contract owner has the right to buy/sell the stock at. With call options, the lower the strike, the more expensive the option. That’s because locking-in the right to buy Ford shares at $7 is more valuable than having the right to buy them at $10.

Put options are the opposite – the higher the strike, the more expensive the option. Having the right to sell a stock at $13 is more valuable than having the right to sell it at $10.

Every stock has numerous strikes available which provides flexibility when structuring trades. You can fine-tune your level of exposure depending on if you buy a cheaper or more expensive strike price.

– Time to Expiration

The next ingredient specifies how much time the contract provides. These days the market lists options that expire anywhere from one day to two years into the future. And that’s a good thing because it allows you to acquire the exact duration of exposure you need. Because a stock can move more over one year than one day, long-term options are more expensive than short-term options.

– Volatility

You can think of volatility as the magnitude of expected price changes in the stock. Are we creating an option for a consumer staple stock like Coca-Cola that exhibits the pulse of a corpse? Or, are we using a high-flying acrobat stock like Tesla that entertains spectators with rip-roaring rallies one day, and deathly descents the next? Since higher volatility stocks have a higher likelihood of delivering big profits to option buyers, they are more expensive. Alternatively, lower volatility stocks boast cheaper options.

Collectively, these first four ingredients form the base of our recipe. They are the “core four” components that drive the entire formula. The final two elements carry much less weight. Consider them the spices.

– Dividends

Some stocks pay dividends as a means of rewarding shareholders. It’s a distribution of profits and is typically paid on a quarterly basis. Because the market is efficient, stock prices usually drop by the amount of the dividend when it’s doled out. That means if a $100 stock pays a $1 dividend its stock price will usually drop to $99 on what’s known as the ex-dividend date. This matters to option pricing because when a stock pays a dividend it reduces the forward price of the stock. The net effect is it drives down call premiums and boosts put premiums.

– Interest Rates

The last, and arguably least important, ingredient is risk-free interest rates. Option premiums are adjusted for something known as the cost of carry. Since the impact of interest rate changes is so small, this is a rabbit hole you don’t need to worry about going down.

Case Study

With a proper understanding of the six ingredients, you are now ready to follow an option pricing example. For today’s creation, let’s craft a call and put option with the following specs:

– Stock price: $11

– Strike price: $10

– Time: 30 days

– Volatility: 60%

– Dividends: None

– Interest Rates: 1.87%

These six items are the inputs to the Black-Scholes model. You can think of it as an option chef’s oven. You place the six ingredients in the model, click a button, and voila! out pops the fair price of an option.

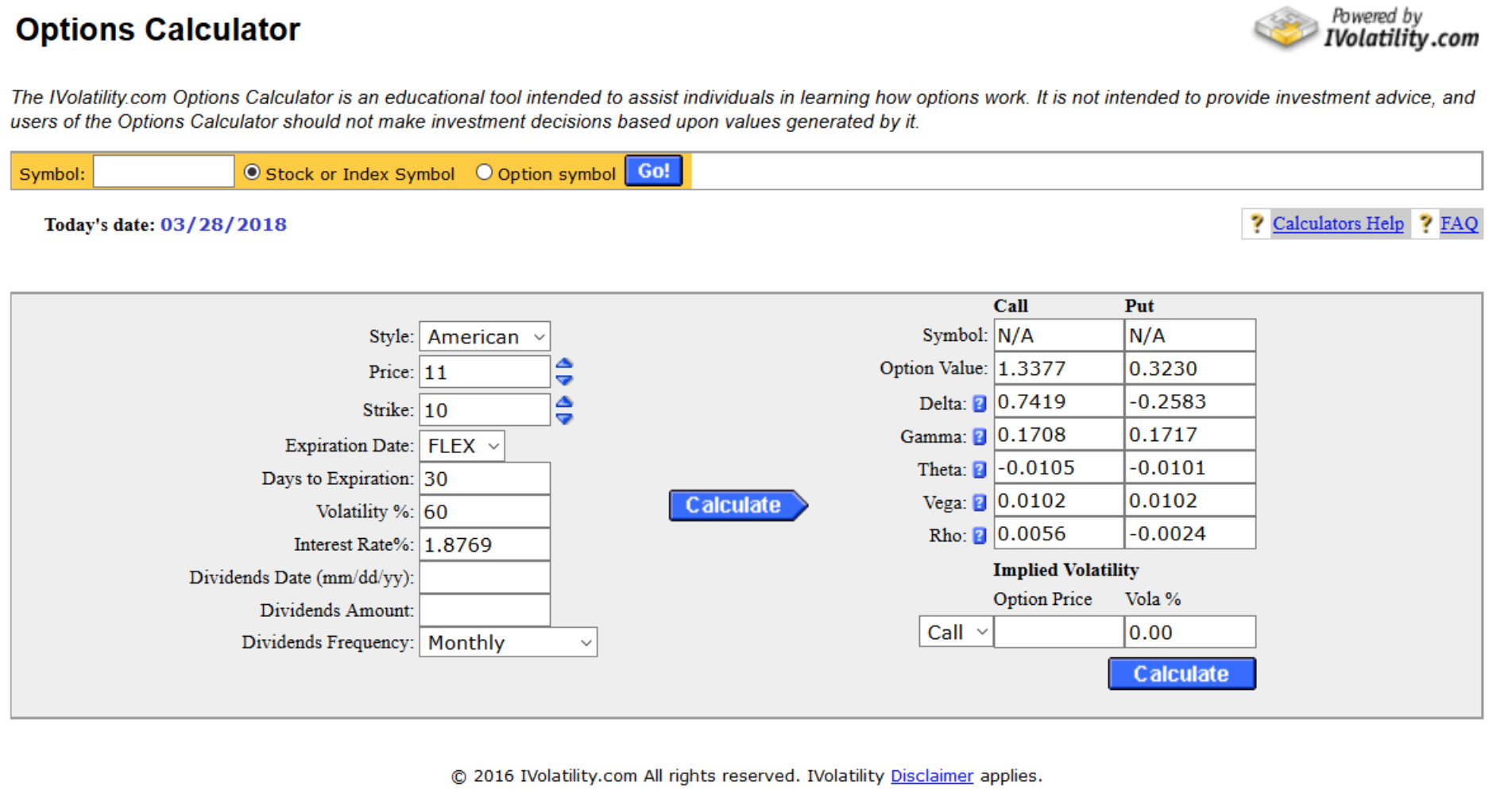

One of the best exercises for fully grasping option pricing is to play with an Options Calculator. There are many of them available online for free. Here’s is a screenshot of the tool offered on the Chicago Board Options Exchange’s website (www.cboe.com). On the left-hand side, you’ll find the six inputs (or ingredients) I listed above. On the right-hand side, you’ll find the prices of the call and put displayed in the “Option Value” row. The calculator also shows the corresponding greeks for both options.

Given our six inputs, the model is saying our $10-strike call will cost $1.34 (rounded up), and the $10-strike put will cost 32 cents.

Congratulations! You officially know how to price an option.

The Option Chain

Your broker should display the respective prices of each option (call and put) on a particular stock in what’s known as the option chain. Since each stock offers an array of strike prices to choose from you will be bombarded with numbers. Each row in the chain represents a different strike, and each column represents a different piece of information about that particular option. What concerns us today is helping you understand the importance of two specific columns – the bid and ask.

Let’s use our $10-strike call that we created above to illustrate. The Black-Scholes model suggested that the fair price for the option should be $1.34. In the world of trading, however, there isn’t one price for an asset. There are two prices – the amount you can sell for and the amount you can buy for. They are known as the bid and ask. For actively traded, liquid products the spread between the bid and ask is narrow. If our $10-strike call was liquid its bid and ask might be $1.33 by $1.35. In this case, the difference between the two (known as the bid-ask spread or bid-ask differential) is 2 cents. Alternatively, if the call was not actively traded (aka illiquid) then the bid and ask might be $1.24 by $1.44. A bid-ask spread of 20 cents for a $1 option is undesirable.

We highly recommend you only play options on active stocks. A good rule of thumb is to focus on those that trade at least one million shares a day.Consider today the initial stepping stone into your option trading journey. We’ve uncovered their history and the details of their pricing. But further discoveries await from additional vocabulary terms to tricked-out tools like risk graphs. And then there’s a veritable buffet of sweet-sounding strategies to choose from like iron condors and inverted butterflies.Keep at it and enjoy the process!