The stock watching class is vast and varied. Some believe markets follow a random walk. Predict the future? Nonsense, they say! Forecasting the market’s next move is like trying to guess the direction of a drunk’s next step as he stumbles down the alleyway. It’s a fool’s errand that makes a monkey of the guesser. Adherents to the random walk theory suggest you should simply invest in stocks for the long run and ignore the day-to-day machinations. Volatility is noise best ignored. Or so they say.

The biggest flaw in this thinking is that markets aren’t, in fact, utterly random. Even a cursory glance of history reveals as much. Patterns repeat, and trends persist with far more regularity than should exist in a completely random world. Inquisitive investors have been analyzing the behavior of stock prices since the dawn of modern markets. And numerous schools of thought have emerged to describe how and why markets move. Some methods make sense, and others are, well, bunk.

Today our attention turns one of the most enlightening ways to view stock prices. We’re talking cycles. Not bi-‘s and tri-‘s mind you, but those of the economic variety. We’ll start with the business cycle. Then we’ll sprinkle in some monetary and fiscal policy theory. For the finale, we’ll tie it all together and show how these forces combine to drive the market cycle.

And don’t worry. We’re going to keep things practical. They’ll be no spelunking in wonky, theory-laced rabbit holes here.

It’s the Economy, Stupid

Stocks are often referred to as equities. And for a good reason. They represent shares of ownership or equity in a company. When you buy shares of Apple Inc., you become a part owner (however small). And as with any business owner the critical metric that determines your success is profits or earnings. If you really wanted to simplify the behavior of stock prices something like this might work:

- Corporate profits rise = stock prices rise

- Corporate profits fall = stock prices fall

Sure, there are a thousand different variables impacting stock prices at any given time. But, in the end, it comes down to profits.

And what, you might ask, drives profits?

As James Carville, campaign strategist for Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 run against George H.W. Bush, so eloquently stated, “The economy, stupid.”

That’s right. If the economy is booming and demand for goods and services is on the rise, then so too are profits. And if the economy is busting causing demand for the products offered by public companies to crater, then so too are profits.

And this isn’t just some sweet-sounding theoretical bunk designed to appeal to your intuition and logic. It’s true! Try this eye candy on for size:

The light blue line reflects the price of the U.S. stock market (S&P 500) over the past ten years. The dark blue line indicates the earnings per share (EPS) over the same time frame. Notice how they tend to move together. Not perfectly, but enough so that we can draw some significant conclusions. Namely, profits and prices have a positive correlation. If profits tank, rest assured stock prices will as well. If they haven’t already, that is. Prices actually lead profits due to their forward-looking, discounting nature.

So, the economy drives profits and profits drive prices.

Perhaps you can now see why Wall Street employs armies of economists and analysts. Forecasting the direction of the economy can do wonders in helping fund managers position their portfolios appropriately.

The U.S. economy has grown over time due to a multiplicity of factors, but two of the big ones are population and productivity.

I. Population Growth

The more workers in a country, the more potential output. It’s really as simple as that. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the current population is 327 million. In the year 1900, it was 76 million. As the number of workers has climbed, so too has our economic output. If you love the economy, if you want to do your part in ensuring future growth, then have lots and lots of babies.

II. Productivity Increases

What’s even better for economic growth than increasing workers is improving the productivity of each worker. With the discovery of new resources and technological advances, productivity has exploded over the past century. Consider, for instance, how many acres a farmer could take care of in 1900 versus today. One genetically enhanced seed throwing, John Deere tractor-driving farmer today can do what would have taken 1,000 farmers to do a century ago. Multiply that over millions of workers in numerous industries, and you start to see why economic growth has been and will likely continue to advance.

While the expansion of the economy has persisted, it hasn’t been without interruptions. Once or twice a decade we’ve seen contractions crop up, otherwise known as recessions. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the authority on this economic cycle and defines a recession as follows:

economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real

GDP (gross domestic product), real income, employment,

industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.”

.

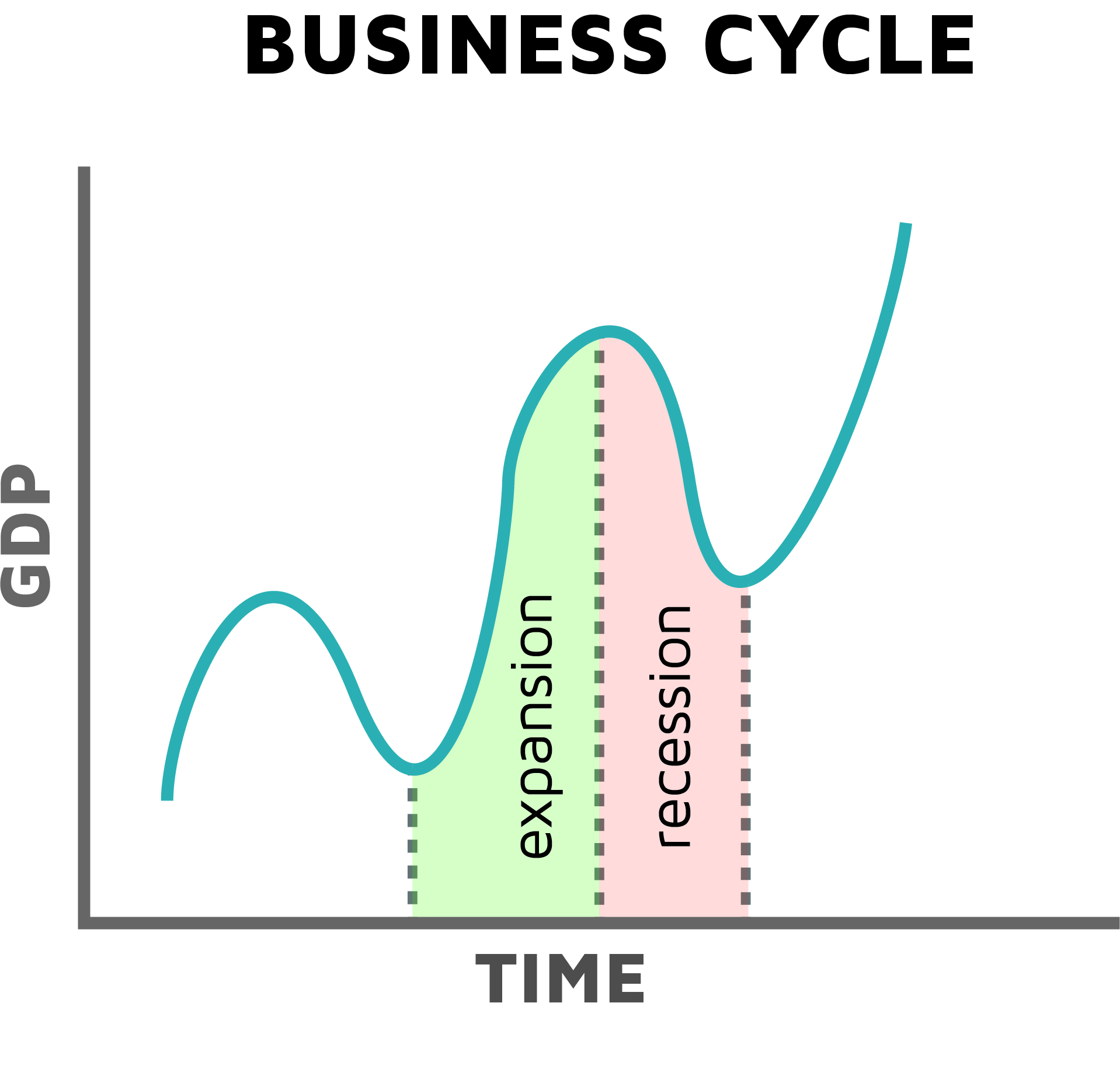

Since that’s a mouthful, many people use a shortcut definition which is two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. The continuous pattern of expansion, contraction, and recovery is known as the business cycle.

Since that’s a mouthful, many people use a shortcut definition which is two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. The continuous pattern of expansion, contraction, and recovery is known as the business cycle.

Because NBER has tracked and dated the business cycle back to 1854, we know the average length of the cycle, including the frequency and duration of recessions. The data encompasses 33 episodes. The average expansion is 38.7 months (3.22 years), and the average recession is 17.5 months (1.5 years). Since the economy post-World War II was starkly different than the decades before, NBER has also calculated the typical cycle in our modern era. Since 1945 the average expansion has been 58.4 months (4.9 years), and the average recession has been 11.1 months (0.9 years).

It’s worth noting that the average duration of these expansions and contractions is just that – the average. Each cycle is unique and irregular. Sometimes a recession strikes three years after the last one and sometimes it hits ten years after.

Here’s the one thing we’re confident in stating: the further away you get from the last recession, the closer you are to the next one. In case you’re curious, the latest recession officially ended in June 2009. That means the ninth birthday of our current economic expansion is fast approaching.

Source: NBER

Let’s summarize the key takeaways:

- The economy drives profits and profits drive stock prices.

- The economy is cyclical, and thus corporate profits are cyclical.

- Corporate profits fall during recessions.

- The worst stock price declines occur when corporate profits fall.

- When the economy recovers, profits and stock prices rebound.

Monetary Policy

According to Wikipedia, monetary policy is,

“the process by which the monetary authority of a country controls the supply of money, often targeting an inflation rate or interest rate to ensure price stability

and general trust in the currency.”

The monetary authority in charge of the money supply in America is the Federal Reserve or “Fed” for short. They are our central bank.

The Fed has two jobs, sometimes known as a dual-mandate: stabilize prices and maximize employment. In other words, they exist in large part to fight inflation and juice the economy when needed so the unemployment rate remains low. They have a variety of tools at their disposal, but one of the most important is interest rates.

By raising or lowering interest rates, the Fed can make it easier or harder to borrow and spend money for corporations and consumers. That, in turn, can help stimulate a sluggish economy or pump the brakes on an overheating one. The interest rate they change is known as the Federal Funds rate. It’s essentially the rate that banks charge other banks for overnight loans. A rise or fall in the rate that a bank has to pay for money will impact how much they charge customers for borrowing money.

Imagine its 2008. The economy is sputtering, corporate profits are falling, workers are being laid off, and unemployment is ramping. The monetary wizards at the Fed spring into action to aid the ailing economy and halt the undesirable rise in unemployment. Between July of 2007 and January 2009, they drop the Federal Funds rate from 5.25% to 0%. As a result, borrowing costs for buying everything from cars and homes to dishwashers and boats declines. The hope is that cheap money will spur economic activity, arrest the decline in corporate profits, and, eventually, bring the unemployment rate back down.

If you’ve been paying attention over the past decade, you know that all three of those outcomes have come to pass.

Now, imagine its 2004. The harrowing dot-com bubble burst and the recession of 2001 are finally in the rear-view mirror, and the economy is beginning to grow once more. Demand for goods and services is on the rise as are asset prices like stocks and real estate. The concern for the Fed begins to shift from maximizing employment to fighting inflation. To stave off the purchasing-power-killing inflation monster, they start raising interest rates. From June 2004 to July 2006 the Fed lifted its Federal Funds rate from 1% to 5.25%.

The rising rate regime of 2004 to 2006 and the falling rate regime of 2007-2009 aren’t unique. This cyclical rise and fall in interest rates have been a part of our economic system ever since the creation of our Central Bank.

Consider, for instance, the following chart which displays the Federal Funds Rate from 1982 to today. Notice the cyclical rise and fall in interest rates as the concerns of the central bank shifted from inflation to employment. To add further insight, we’ve added a big red “R” to flag when economic recessions occurred. It’s no wonder the Fed was slashing interest rates around 1981, 1990, 2001, and 2008!

Though the Fed kept interest rates pinned near zero for some seven years (2008 – 2015), the long-awaited shift toward rising interest rates has commenced (see white arrow at far right). And why shouldn’t it? The unemployment rate which stood as high as 10% in 2008 has now retreated to 4% which is a 17-year low. Like all previous cycles, the pendulum has swung back in the other direction. Inflation is now the Fed’s principal concern.

If history is any indication (and it always is), the rising rate regime that is now upon us will persist until a recession or some other adverse economic scenario arises that tilts the Fed’s concerns back in the direction of employment.

Fiscal Policy

As powerful as central banks are, they aren’t the only player influencing the economy. The government, which spends hundreds of billions of dollars annually, can also sway things. Now we’re entering the realm of fiscal policy which Investopedia defines as “the means by which a government adjusts its spending levels and tax rates to monitor and influence a nation’s economy.”

There are varying schools of thought on the role of government spending and how it should respond to economic recessions. One relevant to our discussion today is Keynesian economics which was the brainchild of British economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes advocated active government intervention during economic downturns. When demand from the private sector was found wanting, and unemployment remained stubbornly high, the government could increase spending to hasten recovery.

History is replete with examples of Keynesian thought spurring politicians to action. The response to the 2008 financial crisis is particularly instructive. As economic conditions deteriorated, and fears of a full-fledged depression grew, the United States Congress jumped into action with the passage of two major bills. The first was the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 which included $152 billion in stimulus. Then came the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 which consisted of $787 billion worth of spending, tax rebates, and business investment.

Combined with the extraordinarily accommodative monetary policies from the Fed, these fiscal measures were successful in staving off a depression and, eventually, leading to a renewed expansion in the economy.

Rest assured there will be another recession. Its inevitable arrival was put into motion as soon as the last one ended. And when it finally shows, you can bet monetary and fiscal policy will play a part in its eventual demise and the birth of a new advance.

I Want to Ride My Market-cycle (Queen Bicycle Race reference)

The impact of the business cycle and the actions of central banks and governments on stock prices is inescapable. Rather than denying the realities of the cycle, why not embrace them? A long-term view of stock prices shows how we alternate between bull and bear markets. It was ever thus, and we are confident this see-saw behavior will continue until the end of time. As suggested previously, most of these bear markets materialized when the economy entered a recession.

Here’s a chart of the Dow Jones Industrial Average since 1942.

You can be strategic in how you invest depending on the current stage of the cycle. Increasing exposure during recessions when asset prices are low and money is cheap makes sense. Decreasing exposure during the late stages of expansion (like now!) when asset prices are high and money is getting expensive is smart. Though interest rates remain well below their levels of decades past, they’ve now risen to ten-year highs. The appeal of risk-taking is getting incrementally less attractive. At the same time, the cost of insurance is as cheap as it’s ever been. They’re almost giving away put options these days. Smart investors use this information to make skillful changes to their portfolios.

Fortunately, you don’t need a Ph.D. in economics to profit from these cycles. Truth be told, if you just picked up what we laid down in today’s newsletter, you already know more than 99% of the population anyways. Paying attention to the right information is half the battle.If you feel like you missed opportunities during the last recession and expansion, don’t worry about it. There’s always another cycle coming around the corner. The million dollar question is will you be ready to profit?