This quarter’s newsletter has one objective: to teach you how taxes on your investments work in plain English. Our discussion will cover three key topics: capital gains, dividends, and account types. Before we begin, a few disclaimers are in order.

First, this is designed to be a beginner’s guide of sorts, not a comprehensive tome addressing all traders and investors.

Second, everyone’s situation is different, and your best bet is to consult an accountant or tax professional. This newsletter will help you get the lay of the land and converse more intelligently with your accountant. It is not designed to replace them!

Third, tax laws and regulations change. Some of the information below will undoubtedly get adjusted in the years ahead. This provides a snapshot of what the four core topics above look like as of January 2023.

On we go.

When you buy stock you are acquiring equity in a company. There are two ways you can make money: price appreciation and dividends. If you buy a stock for $100 and later sell it for $120, you realize $20 of capital gains. The gains were brought to you courtesy of price appreciation. Many companies also compensate their shareholders by paying dividends. Think of dividends as cash income distributed to owners. It’s their cut of the company’s profits.

Suppose you take $10,000 and buy 100 shares of a $100 stock. Later you sell the entire position for $150, netting a $50 per share gain. Your total profit or capital gain is $5,000.

The company also paid out two dividends of $2 per share each while you owned it. That netted you another $400 of profit in the form of dividends.

In sum: $5,000 of capital gains and $400 of dividends.

How much tax you owe (if any) comes down to two crucial questions.

One: What account type do you own the stock in?

Two: How long did you own the stock?

Let’s dig in.

Account Types

When you open a brokerage account, you have a variety of account types to choose from. From a tax perspective, there are three distinct ones: taxable, tax-deferred, and tax-free. The latter two are usually considered retirement accounts.

The first one has no tax advantages and is thus where Uncle Sam extracts the largest toll. We’ll save the tax consequences of that particular account for the end. First, let’s break down the benefits of investing in tax-deferred and tax-free accounts.

Tax-Deferred

This bucket includes an alphabet soup of variations. You’ve undoubtedly heard of at least some of them and may even currently own one. We’re talking about the 401k, 403b, TSP, IRA, SEP-IRA, SIMPLE-IRA, and others. The money you invest in them is considered pre-tax. In other words, the money you contribute to these has not yet been taxed. As such, it reduces your tax burden today. For instance, if you had $100k of earned income but invested $20k of your wages into a 401k, you would only be taxed on $80k of income. If you’re in a 25% tax bracket, that translates into about $5k in tax savings ($20k x 0.25).

That’s the first benefit of using these account types. You save on taxes today.

But that’s not all!

These accounts also grow tax-deferred, which means you don’t have to pay taxes on capital gains, dividends, or interest received along the way. Unfortunately, the tax deferral only goes so far. At some point, you can defer no longer and must start paying taxes on what has hopefully grown to a large nest egg. These are known as Required Minimum Distributions or RMDs.

The logic here is simple. The government let you invest money that has never been taxed. It also let you accrue dividends and interest un-taxed, potentially for decades. But as you enter the final quarter of your life, Uncle Sam finally comes a-knockin’, and it’s time to pay the piper.

As of 2022, the age at which RMDs begin is 72. The recently passed Secure Act 2.0 will shift the RMD age gradually higher to 75 over the next decade. When the time comes, you will be required to begin pulling money out of your tax-deferred account, whether you need it or not. A formula determines how much you must withdraw, and it’s based in part on your account value from the previous year. Since none of the money in the account has been taxed, it’s all viewed the same – as ordinary income, regardless of if it was your original contribution, dividends, capital gains, or interest.

If you’re in a high tax bracket and need to reduce your taxable income, then tax-deferred accounts can definitely come in handy. In the case of a 401k, many employers match the dollar amount you invest up to a certain percentage of your income. So you can get an immediate 100% return. It’s free money. Take it if it’s offered. While some of these are company-sponsored plans that are only available if your employer provides them, others, such as the IRA, can be set up by individuals. There are eligibility limits based on how much money you make, so do your due diligence to ensure you qualify.

Where things really get interesting is if you own your own business. In that situation, you can use accounts like individual 401ks, SEP-IRAs, Simple IRAs, and the like to benefit yourself as a business owner and employee. This gives you much control over your taxable income each year.

Because tax-deferred accounts are designed for retirement, they do have penalties attached that disincentive you to touch the money before you’re old enough (currently 59.5). If you withdraw the money for anything but one of a few exceptions, you will be charged a 10% penalty. And, of course, you’ll have to pay tax on the distribution too.

Here are three strategies you can use with these account types.

First, you can donate the required minimum distributions to charity if you don’t need the money that year. It’s known as a qualified charitable donation or QCD. When done properly, the donated distribution doesn’t count as income to you and thus bears no tax consequence.

Second, if the market crashes at some point between now and when you turn 72, the balance of your tax-deferred accounts will decline, potentially dramatically. While it’s low, consider converting some or all of it into a Roth IRA if possible. The converted amount is taxable that year, but future growth will be tax-free in the Roth IRA. If you must pay taxes on the tax-deferred account anyway, why not do it when it’s temporarily low to reduce the hit?

Third, you could also strategically convert some of the tax-deferred accounts into a Roth IRA in a year where you find yourself in a low tax bracket due to a loss of income, sabbatical, or other reasons. The logic is similar to strategy number two.

Remember the investment above that netted you $5,000 of capital gains and $400 of dividends? If that were held in a tax-deferred account, there wouldn’t be any tax consequence for you in the year the gains/dividends were realized. Instead, that $5,400 would be lumped in with the rest of the account balance and be taxed as ordinary income when you started taking distributions later in life.

Now that we’ve introduced the idea of a Roth account let’s tackle how tax-free accounts work.

Tax-Free

Tax-free accounts are typically referred to as Roth accounts, as in Roth IRA or Roth 401k. As the name suggests, investments in these buckets grow tax-free, meaning you never have to pay taxes on capital gains, dividends, or interest accrued. Unlike the tax-deferred accounts described above, money invested in a Roth account is considered post-tax. In other words, you’re contributing money that has already been taxed. Adding money to a Roth account does not reduce your taxable income today.

For instance, if you had $100k of earned income and invested $20k of your wages into a ROTH 401k, you would still be taxed on the entire $100k. But, and here’s the beauty of it, if that $20k proceeded to grow to $150k over the next two decades, you wouldn’t have to pay a dime of taxes on any of it.

With tax-free accounts, you pay tax on the seed.

With tax-deferred accounts, you pay tax on the harvest.

Because the money in a Roth IRA doesn’t need to be taxed, there are no required minimum distributions. This allows you to keep the money invested tax-free for far longer than in a traditional IRA/401k.

Another perk is that the money is more accessible. Some find the idea of tying up their money until age 59.5 untenable. Roth IRAs provide easier access to the funds. Because the contributions have already been taxed, you can access them at any time, penalty-free. But you should think long and hard about withdrawing the money because it will interrupt future compounding and growth. If you withdraw more than your total contributions, then you’re tapping into the earnings portion of the account, and you may be subject to a penalty.

While not everyone has an employer who offers a Roth 401k, many can still open a Roth IRA through a bank or brokerage like TD Ameritrade, Schwab, or Fidelity. There are two prerequisites to be eligible to contribute to a Roth IRA.

First, you must have enough earned income to cover your contribution. You can’t be retired, have no earned income, and still fund a Roth, for example. Nor can you only have $3k of earned income while placing $6k into a Roth IRA. One exception to this rule is that you can open up a Roth IRA for a non-income-earning spouse.

Second, you can’t have too much income. Uncle Sam discriminates against high-income earners, presumably reasoning that they don’t need/deserve the benefits of a Roth IRA. That said, there is a workaround known as a backdoor Roth IRA, so if you find yourself making too much money, consider this your nudge to explore how it works.

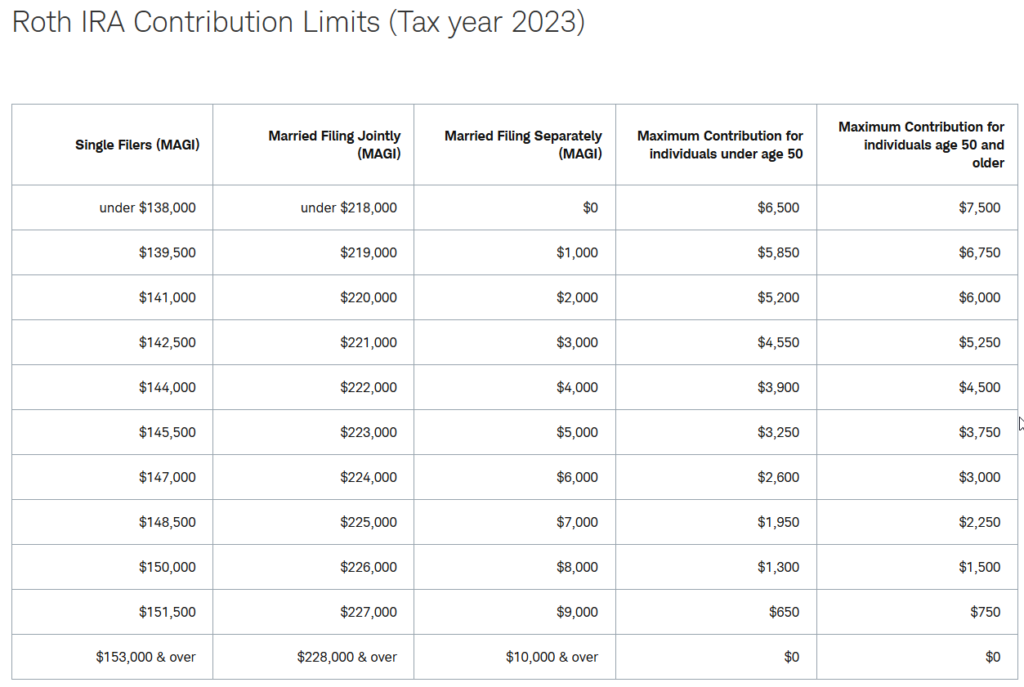

Here’s a table illustrating the Roth IRA income and contribution limits for 2023:

If you’re a married couple filing jointly and make less than $218,000, then you could open a Roth IRA for both of you and contribute $6,500 apiece, or $13,000 total. Thankfully, the IRS adjusts the income and contribution limits every few years for inflation.

Let’s return to the initial investment that netted you $5,000 of capital gains and $400 of dividends. If you owned that in a Roth account, there would be zero tax owed.

Taxable

Taxable accounts are the final bucket and may be used by investors for various reasons. As the name suggests, any capital gains, dividends, and interest received in this account type are taxable. Each year, usually in February, your broker will send you a form 1099 outlining your capital gains, dividends, and interest received in the prior year. You’ll use this when filing your tax return to account for your investment returns properly.

This illustrates the main drawback of investing in a taxable account: the taxes! Year by year, they eat away gains that would have grown unimpeded in a tax-deferred or tax-free account.

But that doesn’t mean taxable accounts are all bad. Here are six unique advantages:

- Liquidity: you can access the money in your taxable account at any time without penalty.

- Flexibility: you can trade any product or strategy. In contrast, retirement accounts have restrictions on certain strategies, like selling naked options.

- Margin: you can borrow money to increase your leverage.

- Shorting: you can make bearish bets by shorting stock.

- Pledged Asset Line (PAL): You can borrow against capital or investments in your taxable account. This is useful if you have a position with a large unrealized gain. Instead of selling it to free up money and incur a large tax hit, you could borrow against it instead. You’re pledging your assets as collateral against a bank loan. This can’t be done with assets in a retirement account.

- Tax Loss Harvesting: When you incur capital losses in a taxable account, they can offset any capital gains and up to $3k of income. Every year, intelligent investors seek to harvest losses to reduce their tax burden. This cannot be done in retirement accounts.

Here are two situations where you might use a taxable account:

First, you’ve maxed out your 401k and Roth IRAs for the year and still have more money to invest.

Second, you don’t qualify for a Roth IRA because your income is too high, and you’d rather have your money liquid than tied up in a 401k.

Suppose you owned that investment that earned you $5,000 of capital gains and $400 of dividends in a taxable account. You most definitely would owe some taxes. The matter of how much depends on a few factors, but two dominant ones are:

- How long did you own the stock?

- What is your tax bracket?

Capital Gains

If you owned the stock for one year or less, your gains are considered short-term and will be taxed at your ordinary income tax rate. This may not sound like a big deal, but it’s a pain for those with a large income because they are taxed at their top marginal rate, which could be as high as 37%. And those are just Federal taxes. There are state taxes, too, depending on where you live.

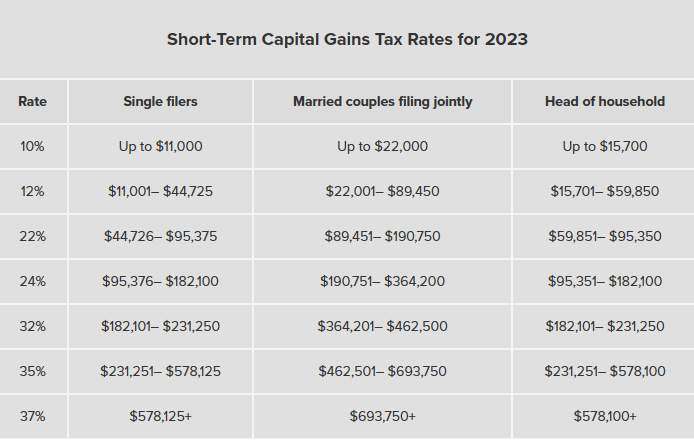

Here are the short-term capital gains tax rates for 2023 by filing status:

So, if your $5,000 gain was short-term and you’re a single filer with $100,000 income, you owe 24% federal tax on your profits. That’s $1,200.

One of the unfortunate side effects of active trading in a taxable account where you’re never holding positions longer than a year is that taxes can take a big bite out of your profits.

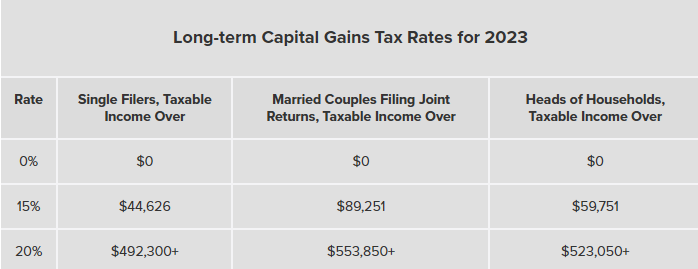

Now, if you owned your stock for more than one year, it would be a long-term capital gain. Here are the long-term capital gains rates for 2023:

By shifting the hold time to more than one year, you reduced the tax rate from 24% to 15%. On your $5,000 gain, you now owe $750.

What about the $400 dividend?

Dividends

The tax rate on dividends varies depending on if they are qualified or non-qualified. Qualified dividends have a more favorable tax rate making them like long-term capital gains. Non-qualified dividends are taxed at your ordinary income tax rate, like short-term capital gains. There are two main criteria to be considered a qualified dividend.

- The dividend is paid by an American corporation domiciled in the United States or a foreign corporation listed on a U.S. stock exchange. Notably, distributions from real estate investment trusts (REITS) and master limited partnerships (MLPs) are not typically considered qualified dividends.

- You owned shares of the dividend-paying company for at least 60 days within a specific 121-day period. According to The Motley Fool, “The 121-day period begins 60 days before the ex-dividend date of the stock, which is exactly 60 days before the next dividend is distributed.”

In this case, let’s assume the $400 dividend was qualified. The actual tax amount owed on qualified dividends is a function of your income. Here’s a table showing the different income and tax levels for 2023:

| 2023 Tax Rate | Single Filers | Married Filing Jointly | Heads of Household |

| 0% | Up to $44,625 | Up to $89,250 | Up to $59,750 |

| 15% | $44,625 – $492,300 | $89,250 – $553,850 | $59,750 – $523,050 |

| 20% | More than $492,300 | More than $553,850 | More than $523,050 |

Using the same single filer making $100,000 a year, the $400 of dividends would result in a 15% tax, or $60.

Thanks for reading!

Legal Disclaimer

Trading Justice LLC (“Trading Justice”) is providing this website and any related materials, including newsletters, blog posts, videos, social media postings and any other communications (collectively, the “Materials”) on an “as-is” basis. This means that although Trading Justice strives to make the information accurate, thorough and current, neither Trading Justice nor the author(s) of the Materials or the moderators guarantee or warrant the Materials or accept liability for any damage, loss or expense arising from the use of the Materials, whether based in tort, contract, or otherwise. Tackle Trading is providing the Materials for educational purposes only. We are not providing legal, accounting, or financial advisory services, and this is not a solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any stocks, options, or other financial instruments or investments. Examples that address specific assets, stocks, options or other financial instrument transactions are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to represent specific trades or transactions that we have conducted. In fact, for the purpose of illustration, we may use examples that are different from or contrary to transactions we have conducted or positions we hold. Furthermore, this website and any information or training herein are not intended as a solicitation for any future relationship, business or otherwise, between the users and the moderators. No express or implied warranties are being made with respect to these services and products. By using the Materials, each user agrees to indemnify and hold Trading Justice harmless from all losses, expenses, and costs, including reasonable attorneys’ fees, arising out of or resulting from user’s use of the Materials. In no event shall Tackle Trading or the author(s) or moderators be liable for any direct, special, consequential or incidental damages arising out of or related to the Materials. If this limitation on damages is not enforceable in some states, the total amount of Trading Justice’s liability to the user or others shall not exceed the amount paid by the user for such Materials.

All investing and trading in the securities market involve a high degree of risk. Any decisions to place trades in the financial markets, including trading in stocks, options or other financial instruments, is a personal decision that should only be made after conducting thorough independent research, including a personal risk and financial assessment, and prior consultation with the user’s investment, legal, tax, and accounting advisers, to determine whether such trading or investment is appropriate for that user.