Wall Street sits at the nexus of countless crosscurrents. News, fundamentals, sentiment, economics, politics – you name it. They are ever-present, constantly competing for investors’ eyeballs. The information barrage can quickly overwhelm the newcomer. These dream-toting, starry-eyed rookies arrive, like clockwork, each morning to try their hand at the great investing game. With pockets (some big, some small) full of cash and a desire to grow wealth, they possess the perfect – indeed necessary – prerequisites to play.

Unfortunately, menacing misinformation abounds. It’s a threat to their adventure from the outset. If there’s one thing that Wall Street lacks, it’s consensus. There is no field guide with foolproof practices and a one-size-fits-all strategy. Instead, there are sweet-sounding and seductive opinions whispered by a colorful cast of characters, not the least of which are those well-meaning but woefully ignorant acquaintances. Some call them friends. Others call them family. Their advice is usually (but not always!) worth the price you paid them. That is, nothing.

This month’s newsletter is the caboose of 2020. In this, the last of a dozen wisdom-laced messages, we’re exploring a topic that many misunderstand – how to build a long-term investment portfolio.

Rare is the person who understands how to do it. Rarer still is the human who can articulate it. Herein lies our attempt.

The Difference Between Investing and Speculating

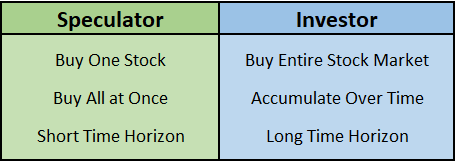

To follow our explanation to completion requires a proper understanding of vocabulary. For instance, what is the difference between investing and speculating? No doubt you can come up with a few synonyms or offhand definitions.

Speculating: gambling, guessing, risky, requires a higher skill set, focused on the short-term.

Investing: safer, rooted in sound practices, advocated and defended by institutions and stewards of capital, focused on the long-term.

Opinions can vary on the core differences, but here’s an undeniable truth. Speculation almost always carries a lower probability of success. For many, it is a desperate gambit to score big. That’s not to say that all speculators are haphazardly rolling the dice. A select few systematize their craft and do all in their power to elevate the odds. Unfortunately, these are the exceptions.

Investing, on the other hand, provides a higher chance of generating profits. At least, it does if you do it right! Sadly, many confuse the two. They’re speculating when they think they’re investing. Worse yet, when they fail, they may unjustly conclude that investing doesn’t work.

But that’s not true. Your form of “investing” (if it even was that) didn’t work. Far from being a reason to give up, that should be the catalyst that empowers you to seek more knowledge.

Here’s what this looks like in practice.

Jane: The Speculator

Jane reads a news article about three interrelated and positive facts regarding Tesla. First, it was added to the S&P 500, signaling what was once a cult stock has become mainstream. Two, its price chart boasts powerful momentum and accumulation days galore. Third, Elon Musk is a handsome devil. With freshly fueled conviction, she promptly acquires TSLA shares the following trading session.

Not two weeks later, Tesla’s share price inexplicably sinks 20%. This happens, mind you, while the S&P 500 rose 2%. There was no news, just supposed “profit-taking” by Tesla traders. Nonetheless, Jane is spooked and exits her position with curses beneath her breath. Screw stocks, she reasons. I’ll try my hand at cryptocurrencies.

Larry: The Investor

Meanwhile, Larry builds a budget and discovers he can sock away $500 a month to invest for his retirement 15 years away. Since the venerable Jerome Powell and Company has made cash trash with their zero interest rate policy, Larry rightly reasons that saving in the bank is foolish. The opportunity cost is too high. Furthermore, he already has an emergency fund and three-months of savings squirreled away.

He decides to invest in an asset class that has historically generated a higher return than every other alternative. It’s not real estate or precious metals. Nor is it bonds or T-bills. It’s stocks, glorious stocks. It turns out that the fastest way to build your wealth has been to buy equity in the best companies on the planet.

Larry realizes the only way to get what the stock market is willing to give is to buy it in its entirety, rather than betting on a single stock. Thus, he builds a globally diversified stock portfolio using low-cost exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

Rather than living and dying by a single month’s purchase, he views each acquisition as one in an endless stream. If he buys once per month over the next 15 years, he will have 180 total purchases. Do you think it matters if the market rises or falls after any one or two or ten of those? No.

Now, take a moment and list what you think made Jane a speculator and Larry an investor.

Then, please read below for our answers.

Diversification

The first and most obvious difference between the two is diversification. Let’s be clear – buying a single stock is not investing; it’s speculating. Jane was not investing in the asset class of equities. Instead, she was betting that Tesla would not only keep pace with the performance of the stock market but exceed it. This is the implicit bet anytime you purchase an individual company.

Too many traders erroneously think the way you “invest” in equities is to pick a single stock. It’s not.

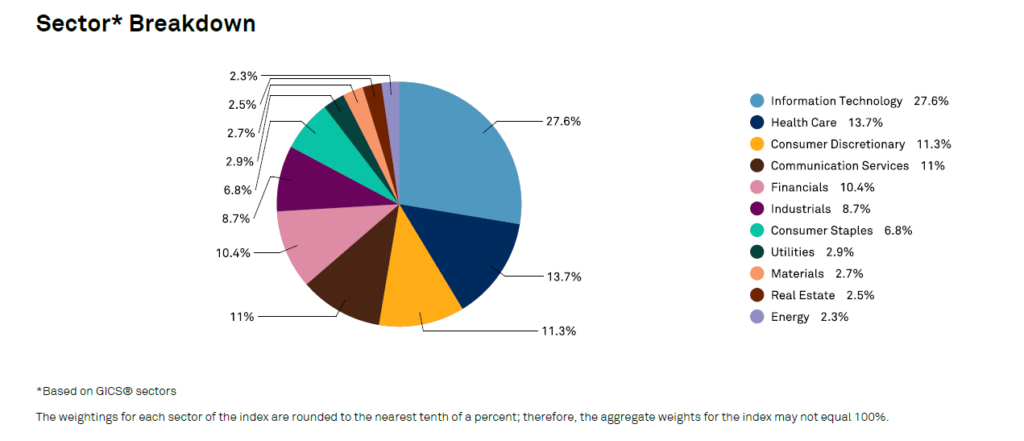

Larry understood this. He bought the entire stock market using the S&P 500, which boasts the biggest 500 companies in America. Were he to take it a step further, he could have also purchased a foreign stock fund. That said, the companies comprising the S&P 500 generate over 40% of their annual sales from foreign countries, thus providing global exposure.

Additionally, the S&P 500 offers exposure to every single sector. By contrast, Jane only had exposure to technology through Tesla.

Source: S&P Global

Suppose Jane took her stock-picking a step further and selected five stocks instead of one. And we’ll be generous and assume she spread them over five different sectors. Is she still a speculator? Yes. But, less so. The broader her basket, the closer she gets to investing in stocks as an asset class. However, she’s still betting that her bucket of five will outperform the S&P 500.

And therein lies the problem.

It’s not an insurmountable problem, mind you. But it’s one that requires skill and experience. Does Jane have a track record of picking stocks that beat the market? She had better. Otherwise, it’s unwise, and she’s probably better off purchasing something like the S&P 500.

Time Frame

A second crucial difference between Jane and Larry was their respective time frames. While Jane was wagering that Tesla would rise over a few weeks, Larry was banking on the stock market climbing over 15 years. But we could argue his hold time was even longer. When Larry retires, he doesn’t need a pile of cash; he needs an investment portfolio that will outpace inflation. And, historically anyway, stocks have done far better than the alternatives at doing so. Thus, even though retirement is 15 years away, his anticipated time horizon could stretch over multiple decades.

There’s a Grand Canyon of difference between betting a single stock will rise over a few trading sessions and wagering that the global stock market will increase over the decades. One has odds that mirror a coin flip. The other is all but guaranteed.

Which would you prefer?

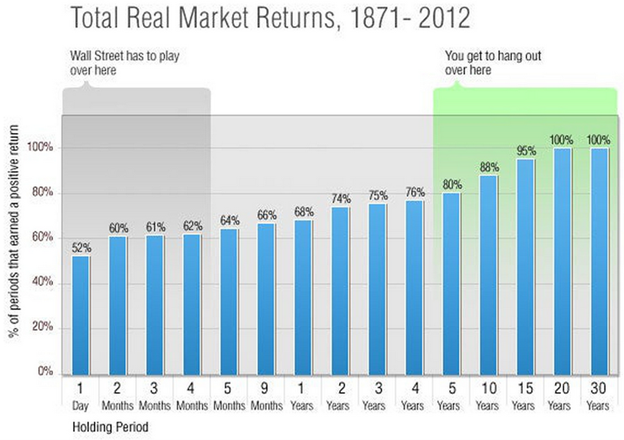

To bolster your understanding of equities’ tendency of rising over time, consider the following graphic. I came across it while reading a Morgan Housel article at Motley Fool.

Source: Robert Shiller, Morgan Housel’s calculations. 1-day returns since 1930, via S&P Capital IQ.

The vertical axis shows the percentage of periods that earned a positive return. The horizontal axis shows varying holding periods, ranging from 1 day to 30 years. When it says “Total Real Market Returns,” it’s looking at the entire stock market and adjusting for both dividends and inflation.

Do you notice the trend? The longer your hold time, the higher your odds of capturing a profit. Larry, the investor, is playing on the right side of the graphic. By contrast, Jane was toiling on the left side.

Number of Purchases

The final difference of note between Jane and Larry involves the number of purchases. When you only buy once, you give great power to the purchase price. Your future gains or losses are anchored on that singular decision. As such, the timing of your entry order is everything.

What if, like Larry, you instead bought 180 times over fifteen years. The considerable number of individual purchases effectively renders timing irrelevant. Instead, what matters is the general trend of prices over time. As long as the value of the asset you are averaging into rises in the long run, then your incremental investments will grow.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results, but historically the S&P 500 has a 100% track record of recovering from every downturn. That means all investments into it, no matter how ill-timed the entry, eventually have made money.

A Better Way

Rookies should replace the question, “which stock should I buy” with “which portfolio should I build?” After they learn new strategies and prove they can enhance their returns, then they can deviate from the baseline portfolio. Too many traders think the path to success starts with picking the best stock or perfectly timing the market. They make what could have been an easy endeavor into a challenging one.

There are many free tools online that provide sample portfolios using low-cost funds for investors of all risk tolerances. You can find the one we’ll use to create the examples below can be here: https://www.blackrock.com/tools/core-builder/us#/

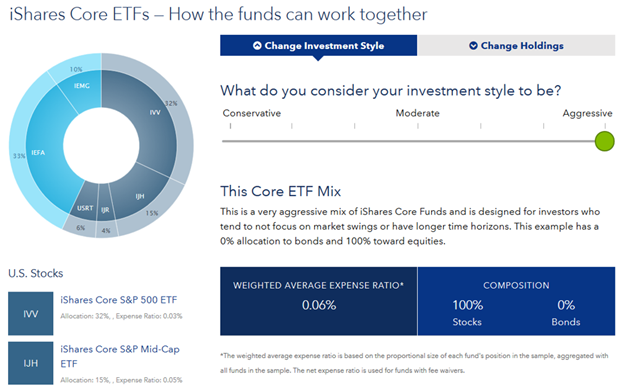

Suppose you’re an aggressive investor with a high-risk tolerance and looking to invest money that you don’t need for at least five years. BlackRock suggests the following asset allocation:

To successfully hold an all-stock portfolio, you must be willing to experience the occasional bear market where your account value temporarily declines 30% (on average). If such harrowing episodes would cause you to sell everything, then a 100% allocation to stocks is inappropriate.

Consider the portfolio above the baseline for a new aggressive investor. It is his starting point, if you will.

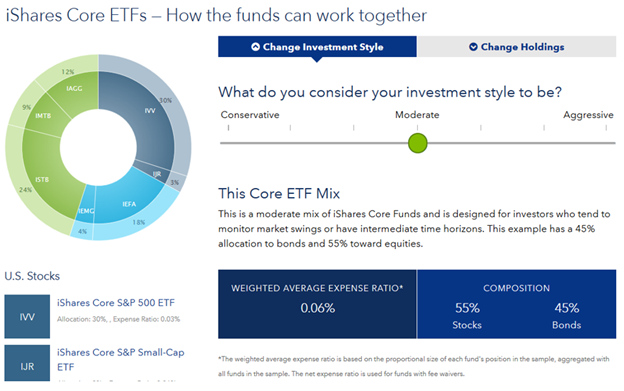

For a moderate investor with lower risk tolerance, the following portfolio would be more appropriate:

Note how the 100% stock portfolio shifts to 55% stock and 45% bonds. The nasty bear markets mentioned above that drove the all-stock portfolio down 30% would only sink this one by approximately 15%.

A new, moderate investor could consider the above asset allocation their baseline. In other words, if they wanted to invest in a less risky mix of stocks and bonds, they could use this or something similar.

Whether they’re investing one thousand dollars, one hundred thousand dollars, or one million dollars is irrelevant. Instead, it all comes down to risk tolerance, and again, the assumption that this is a long-term investment.

Now, if you think you can craft a carefully curated portfolio using individual stocks or various options strategies, then prove it. Once you’ve got the track record and chops to justify deviating from the above, then feel free to do so.

Most people would be better served by putting the bulk of their investment capital in the types of portfolios outlined above and then speculating with a smaller portion at first. Look at it as seed capital to create a proof of concept. It’s better to discover you lack the skills needed to actively pick stocks or time the market with 10% of your hard-earned money than 80%.

As your skills grow and you prove you can do consistently better than the baseline portfolio, you could allocate additional capital to the more speculative approach.