This month’s newsletter is taking a turn into the fascinating field of interest rates. There’s an entire cottage industry on Wall Street dealing with the topic, and we’re going to introduce you to it. Rather than bore you with mind-numbing minutia and sleep-inducing statistics, however, we’re taking the practical route.

You will depart with a better understanding of how interest rates impact financial assets and, more importantly, how they affect you as both a consumer and an investor. To help connect the dots and make this a more stimulating experience, we’ll include a few thought exercises along the way.

What are Interest Rates?

Think of money as a good like milk or butter. Milk has a price tag that rises or falls depending on multiple variables (like supply & demand, consumer preferences, and available substitutes). Money acts similarly, but its price tag is interest rates.

When interest rates rise, money becomes more expensive. Said another way, the cost of money is higher.

When interest rates fall, money becomes cheaper (the cost of money is lower).

Here’s your first thought exercise. Think about the domino effect of changing the cost of money. How would that change your behavior as a consumer? How would it change you as an investor?

If there were a singular interest rate that defined the cost of money for all occasions and purposes, this would be a straightforward story. But there isn’t. And this, dear friends, is where the plot thickens. The cost of money varies greatly depending on numerous factors like:

- Who’s borrowing it?

- Who’s lending it?

- How long is the loan?

- What’s it being borrowed for?

- What is the opportunity cost?

- What are inflation expectations?

Let’s take a brief look at three of these queries.

Who’s borrowing it?

Would you charge the U.S. government the same amount of interest for money borrowed as you would some third-world country ruled by a warlord? Of course not. One boasts a much more stable economy and has decades of sterling credit history. The other one is dangerous.

What if the comparison was Apple Inc. versus J.C. Penny?

Or perhaps Bill Gates versus someone who just declared bankruptcy?

The price of money differs depending on the credit history and stability of the borrower. All lenders gauge the risk of the borrower and shift the interest rate accordingly. High-quality customers pay a lower cost for money than low-quality ones.

How Long is the Loan?

The length of a loan impacts the interest rate for two primary reasons: risk and inflation. Generally, the risk of something bad happening over the next ten years is greater than the risk of something bad happening over the next ten days. Thus, if I’m lending your business money for a longer period, I’ll likely demand higher interest than if I was doing so for a few months.

A second reason for long-term loans carrying higher interest than short-term ones is inflation. Inflation is a long-term phenomenon. It erodes purchasing power over time, not overnight. Thus, if I’m lending you money for a few days, then inflation risk is virtually nil. But, if I’m loaning you money for ten years, then inflation is a genuine concern. You must pay me enough in interest (i.e., the cost of money must be high enough) to compensate me for the purchasing power loss I will experience over that decade.

What are Inflation Expectations?

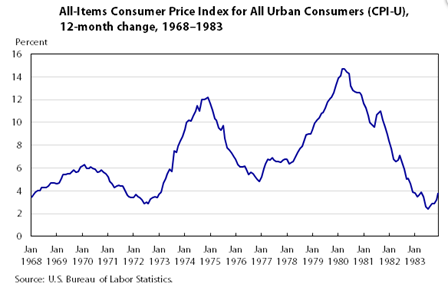

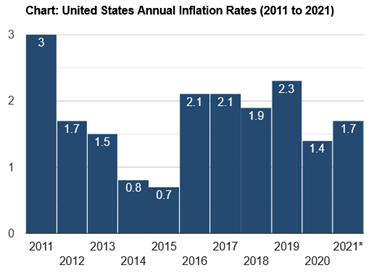

In economics, inflation is a general rise in the price of goods and services over time. But it’s not static – it fluctuates depending on various factors. Multiple years in the 1970s saw over 8% inflation. In contrast, the past decade has averaged less than 2% inflation. If you expect to lose 8% in purchasing power annually, wouldn’t you demand greater compensation when lending money than if you only expected to lose 2% purchasing power? I would!

This is the reason why inflation expectations and interest rates move hand in hand. Let’s look at a few charts to illustrate.

The first graphic shows Wall Street’s favorite inflation indicator (the Consumer Price Index, or CPI) from 1968 – 1983. Note how inflation rose as high as 14% before finally cooling in the early ‘80s.

The past decade, by contrast, has seen extremely low readings.

The tame inflation numbers work to the benefit of borrowers because it puts downward pressure on interest rates. Do you think the cost of capital would have hit record lows and allowed millions of homeowners to refinance at these bargain levels if inflation was running hot like the ‘70s?

No chance.

Now that we’ve elaborated on a few of the questions that drive the cost of money let’s move into the actual interest rates that the investors use.

Fed Funds & Bonds

The two rates that you’ll hear the most chatter about on Wall Street are the Fed Funds rate and bond yields

The Fed Funds Rate

Think of the Fed Funds Rate as the cost of money for overnight loans for a bank. By law, banks (aka depository institutions) must maintain a certain percentage of their deposits in reserve. If they are running below their reserve requirements on any given day, they can borrow money overnight from another bank or the Federal Reserve. The interest they must pay on the loan is known as the Fed Funds rate.

This interest rate affects all others. If a bank has to pay 3% to borrow money, do you think it will lend it to you at 2% for a mortgage, auto loan, or line of credit? Not a chance. They’re in the business of borrowing money at lower rates than they lend it out. Not the other way around. Currently, the Fed Funds Rate is at zero, effectively allowing banks to borrow money at no cost. In turn, they pass on some of the savings to borrowers through lower-priced loans.

If the Federal Reserve raised the Fed Funds rate, it would ripple across the entire interest rate ecosystem, raising costs across the board.

Perhaps you’ve heard the old phrase that a rising tide raises all boats, or its twin – that a falling tide lowers all boats. In the world of interest rates, the Fed Funds is the tide, and mortgage rates, auto loan rates, bond yields, and darn near every other borrowing cost are the boats.

Treasury Bond Yields

Do you know where the U.S. government gets all that money they spend? Tax revenue covers some of it, but Uncle Sam doesn’t rake in nearly enough to cover his profligacy. He borrows the rest through the issuance of bonds. And since it is the U.S. Treasury that is doing the issuing, these debt instruments are called treasury bonds, or T-bonds for short.

Each bond has a maturity date that specifies when the bond owner is repaid the face value. The government issues bonds that mature anywhere from one month to 30 years into the future. Those with a maturity of one year or less are known as Treasury bills. Those with a maturity between one year and ten are called Treasury notes. Finally, those with a maturity longer than ten years are called Treasury bonds.

Typically, bonds pay interest to lenders. The interest rate is sometimes referred to as the bond yield. Based on the logic previously introduced, long-term bonds usually pay higher interest (that is, they have a higher yield) than short-term bonds.

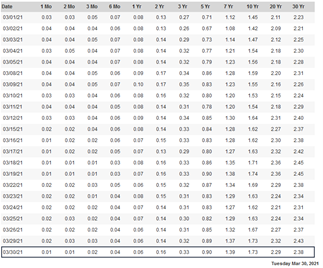

You can track how the rates vary across different maturities by visiting this treasury.gov website. Here is a screenshot. Each column after the first one represents a different maturity. The chart is updated with a new row each day to reflect how the yields have changed over time. I took this picture on March 30th, 2021, so the rates at the bottom are the most up-to-date.

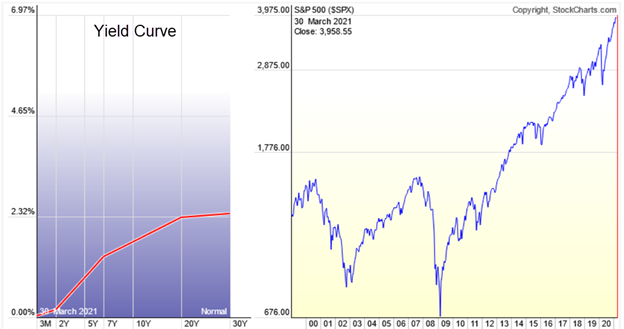

Note how the interest rate is below 1% until the 7-year Treasury note. There is a link between the Fed Funds rate and the yield of short-term bonds (think back to the tide and the boats). The Federal Reserve has said it isn’t planning on lifting rates off of zero until at least 2023. And even then, we’re likely talking about a quarter-point hike. This, more than anything else, is why bond yields don’t rise past 0.25% until you reach the 3-year Treasury note.

As we move out to longer-dated maturities, you’ll discover that the biggest driver of yields is inflation expectations. The reason is intuitive. As mentioned earlier, investors demand compensation for loss of purchase power. For example, if inflation is expected to run at 4% on average over the next three decades, why would anyone lend money to the government at 1%?

They wouldn’t.

The current 30-year yield of 2.38% may not seem like much, but it was sitting in the cellar at 1% just one year ago. We’ve seen a dramatic rise in long-term rates on a percentage basis. This has come amid hopes of an economy reopening and a general lift in inflation expectations.

If you prefer pictures over statistics, then I suggest using the dynamic yield curve tool on stockcharts.com. It presents the same information as the table above, but graphically. Here’s a screenshot of the curve displayed beside the S&P 500.

Borrowers Heart Cheap Money

Which interest rate impacts you most ultimately depends on if you’re a borrower or a saver. We could also juxtapose this as consumers versus investors. While borrowers want low interest rates, savers desire high ones. But it’s not exactly that simple because most individuals sit on both sides of the ledger simultaneously. For instance, I am a borrower (mortgage on the house) and a saver. On the borrowing side, I cheer low interest rates. When I purchased my first house after getting married in 2008, my interest rate was 6.5%. Now, it’s 3%. I’ve refinanced half a dozen times since then, each time reducing the overall interest cost.

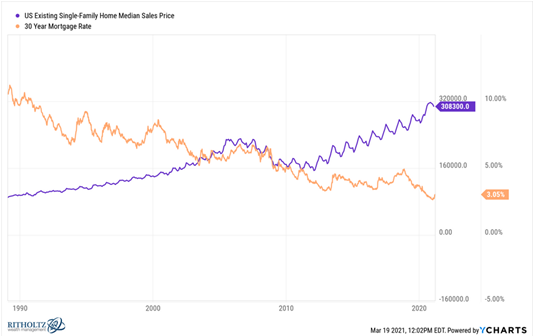

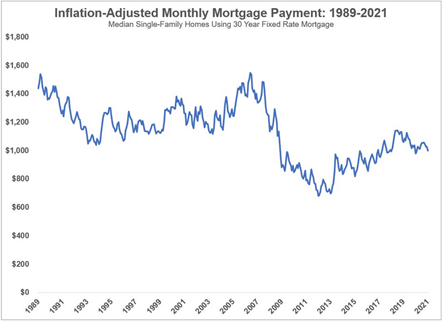

Let’s stick on this for a minute. Housing affordability has been a big issue in the wake of the pandemic. In my neck of the woods (Utah), supply is tiny and demand huge. Houses are sold for tens of thousands of dollars over the asking price, sometimes sight unseen. The median house price in the U.S. over the past few decades has risen considerably. In 1989, it was just over $80,000. Now it’s north of $300,000 – a rise of over 240%.

However, just because the price is up 240% doesn’t mean that the cost is up that much. Here’s what I mean. Interest rates have tumbled over the past three decades.

The 30-year mortgage rate was around 10% in 1989. Now it’s near 3%. The price tag of money is way, way lower than it was. As a result, you can afford a lot more house for the same mortgage payment. Here’s the ringer stat. According to Ben Carlson of Ritholtz Wealth Management, “After adjusting for inflation and interest rates, monthly mortgage payments are now 30% lower than they were in 1989.”

I find this utterly fascinating. And it’s a compelling tale that shows just how powerful a shift in interest rates can be.

In case it wasn’t obvious, low interest rates support the real estate market. It will be interesting to see how prices grapple with rising rates if and when we ever see a sustainable rise.

Homeowners aren’t the only ones using low rates to their advantage, though. Corporations are doing it, too, via the bond market. Just as the government issues bonds via the treasury, corporations from Apple and Microsoft to General Electric and Boeing also borrow in the debt market, creating what is known as a corporate bond.

According to the Federal Reserve and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, or SIFMA, U.S. corporations have amassed $10.5 trillion in debt. It’s a new record. Through the intelligent use of this cheap capital, corporations have been able to boost earnings per share. This is one of the ways low rates have aided the stock market.

Savers Shun Low Rates

The low cost of money, while a boon for borrowers, is a bane for savers.

Here’s another thought exercise. How would you behave differently if you could get 10% interest in a savings account versus 0%?

Savers detest low rates, and I don’t blame them. Suppose you have a $1 million nest egg squirreled away for retirement. In 2007, savings accounts yielded 5%. You could have taken zero risks by placing your cash into a bank and still generated $50k in income. Today, that same dollar amount in a savings account will net you a paltry $5k a year – and that’s if you’re lucky.

In a low interest rate environment, savers are forced to become investors. Of necessity, their search for yield pushes them farther along the risk spectrum into bonds and stocks. Even risky, so-called junk bonds don’t even generate much these days. Once upon a time, these spit off high single-digit, if not double-digit percentage dividends. Now, they’re less than 5% (see HYG or JNK).

The flood of return-seeking capital into stocks and other risk assets is another way that cheapening the cost of capital supports the financial market.

The Competition for Capital

The financial market hosts a wide and varied crew of participants. Each brings unique investment objectives, personalities, and risk tolerances to the table. But one thing they all share is the desire to get the best return possible for each unit of risk taken. For that reason, all asset classes compete for capital.

One reason why investors track interest rates is that it allows them to understand better the backdrop against which other asset classes should be judged.

It’s like a beauty contest where the appeal of each contender changes alongside interest rates. When short-term rates are zero (like now), cash (which is synonymous with a savings account, money market account, or short-term treasuries) loses out to stocks head-to-head every time. Picture Sloth from The Goonies going up against a supermodel.

But do you know what happens as interest rates rise?

High rates turn cash from trash to treasure. Sloth, slowly but surely, becomes the hot girl.

And with that lovely little visual dancing in your head, we’ve arrived at the end of this month’s adventure.

Legal Disclaimer

Trading Justice LLC (“Trading Justice”) is providing this website and any related materials, including newsletters, blog posts, videos, social media postings and any other communications (collectively, the “Materials”) on an “as-is” basis. This means that although Trading Justice strives to make the information accurate, thorough and current, neither Trading Justice nor the author(s) of the Materials or the moderators guarantee or warrant the Materials or accept liability for any damage, loss or expense arising from the use of the Materials, whether based in tort, contract, or otherwise. Tackle Trading is providing the Materials for educational purposes only. We are not providing legal, accounting, or financial advisory services, and this is not a solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any stocks, options, or other financial instruments or investments. Examples that address specific assets, stocks, options or other financial instrument transactions are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to represent specific trades or transactions that we have conducted. In fact, for the purpose of illustration, we may use examples that are different from or contrary to transactions we have conducted or positions we hold. Furthermore, this website and any information or training herein are not intended as a solicitation for any future relationship, business or otherwise, between the users and the moderators. No express or implied warranties are being made with respect to these services and products. By using the Materials, each user agrees to indemnify and hold Trading Justice harmless from all losses, expenses, and costs, including reasonable attorneys’ fees, arising out of or resulting from user’s use of the Materials. In no event shall Tackle Trading or the author(s) or moderators be liable for any direct, special, consequential or incidental damages arising out of or related to the Materials. If this limitation on damages is not enforceable in some states, the total amount of Trading Justice’s liability to the user or others shall not exceed the amount paid by the user for such Materials.

All investing and trading in the securities market involve a high degree of risk. Any decisions to place trades in the financial markets, including trading in stocks, options or other financial instruments, is a personal decision that should only be made after conducting thorough independent research, including a personal risk and financial assessment, and prior consultation with the user’s investment, legal, tax, and accounting advisers, to determine whether such trading or investment is appropriate for that user.