The decision to invest money in the financial markets is a momentous one, not to mention life-changing. It begins a journey of discovery that introduces you to a vast world of profit-generating assets. But before you can put a single penny into stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, you first have to open up a brokerage account. 💰

Fortunately, it’s an easy process that can be completed online within a few short minutes. After inputting your personal information the first question greeting you is:

“What type of account do you want to open?”

Making the right choice requires at least an elementary understanding of the characteristics of each account type. And that, friends, will be the focus of this first half of this month’s newsletter. We’ll explore when and why it’s appropriate to use five of the most common accounts: Cash, Margin, Traditional IRA, Roth IRA, and Solo 401k. This won’t be a comprehensive overview, mind you. Instead, we’ll provide a trader’s perspective on how each account type comes in handy.

One more note before we dive in. Each broker may vary slightly in the verbiage used to describe each account type. Our explanations and definitions focus on those offered by TD Ameritrade.

.

Let’s begin our investigation with a look at individual accounts. For most traders, this will be the first account type that you open. Here’s how TD Ameritrade defines it:

“An individual account is a standard brokerage account with only one owner.”

The majority of brokers have no account minimums so you can open up an individual account whether you’re starting with $50 or $50,000. Furthermore, there aren’t any contribution caps so if you’re a high roller and want to toss a couple million in then your broker will happily accept.

Somewhere along the way of filling out your account application, you will be asked if you want to open up a cash or margin account.

We highly recommend opening up a margin account for two reasons.

- First, it opens the door to trading more capital.

. - Second, it gives you the ability to sell stocks short.

If you’re interested in trading options, you’ll also want to request options trading privileges at some point along the way.

With a margin account, you can borrow money from your broker to purchase marginable securities like stocks. Typically, you can double your buying power using margin so if you deposit $10k in a margin account you can purchase up to $20K of stock.

Buying on margin does carry additional risk and should only be considered by experienced traders. This may be a topic we pick up on in a future newsletter.

Retirement accounts are worthy of consideration given their favorable tax treatment. Many savvy investors use these in addition to their margin accounts. Because tax laws are always changing we highly recommend consulting a tax professional when making decisions about which type of retirement account best fits your situation. Let’s look at three of the more popular ones: Traditional IRA, Roth IRA, Solo 401k.

Traditional IRA

The allure of this type of retirement account is it provides an immediate tax benefit. Money placed in a Traditional IRA is tax deductible. You’re putting in pre-tax money, in other words. Currently, up to $5,500 of tax-deferred earned income (per year) can be placed in the IRA, at least until you reach the ripe old age of 70½. And (bonus!) you can put an additional $1,000 in per year if you are age 50 or older. And (double bonus!) you can contribute an extra $5,500 of earned income per year to a separate IRA for a non-income-earning spouse.

With few exceptions, you can trade the money invested in your IRA the same way you trade your margin account. Again, the primary benefit is you get a tax benefit.

Roth IRA

Unlike the Traditional IRA, contributions to a Roth IRA are not tax deductible. The money you’re putting in has already been taxed, in other words. But here’s the benefit. These contributions won’t be taxed again, and any earnings in the account will grow tax-free. Additionally, the ROTH is more flexible than the Traditional IRA. You can withdraw any of your contributions tax-free.

The contribution limits to the Roth are the same as those outlined in the Traditional IRA. Traders in a low tax bracket generally prefer the Roth, while those in a high tax bracket prefer the Traditional IRA.

As you age and your income grows the annual contribution limit ($5,500 or $11,000 per couple) will really hamper your ability to sock away the dough for retirement. That’s where the next account type comes in handy.

Solo 401k

Traders running a sole proprietorship, partnership, or incorporated business (like an LLC or S Corp) can set up a Solo 401k. The contribution limits are much, much higher allowing high income, tax-reduction-seeking individuals to squirrel away a ton of earned income.

Like the Traditional IRA, contributions to the Solo 401K are tax-deductible and can be invested using the majority of trading strategies available in an individual trading account.

As you grow as a trader and as your assets accumulate you will probably open additional accounts. This allows you to tap into the advantages offered by each account type. While multiple accounts bring more paperwork and increase the hassle-factor, it also provides greater levels of organization and creativity. For example, you might have one account earmarked for short-term trading and another one for long-term investments. Perhaps you focus on aggressive, leveraged strategies in one while using another for conservative wealth-building.

Now that we have a general idea of the primary account types let’s talk about the different investment products used by the masses like mutual funds and exchange-traded funds. Most importantly, we’ll discuss the destructive impact of high fees.

Friends Don’t Let Friends Buy Mutual Funds

Wall Street is in the business of selling products and collecting fees. For the lion’s share of the public, the “product” they’ve bought is a mutual fund, and the fees they pay are, well, obscene. If you have a company-sponsored retirement plan, such as a 401k, TSP, 403b and the like, then chances are the vehicle you’re using to invest in stocks, bonds or any other asset class is a mutual fund.

Wikipedia defines a mutual fund as follows:

A mutual fund is a “professionally” managed investment fund that pools money from many investors to purchase securities.

The term “securities” is usually referring to stocks and bonds. Like any investment product, the mutual fund boasts pros and cons. But when you really get down to it there is one modest advantage and a host of disadvantages. Perhaps the biggest appeal of a mutual fund, its sole strength, is it allows individuals to acquire diversification even if they’re investing small amounts of money.

In a world, without mutual funds (or any of their modern-day equivalents) a diversification-seeking investor would have to manually buy shares of ten or thirty or one hundred different companies. Such an endeavor would be expensive, time-consuming, and inefficient. It would be impossible for our disadvantaged investor to contribute small dollar amounts each month to his investments.

Because a mutual fund pools money from thousands, even millions of investors, it can create the diversification that an individual can’t. And since most mutual fund shares trade for less than $100, everyday mom and pops can afford to invest in the market on a regular basis.

If our story ended here, it would be one of the happy ever after variety. But, alas, mutual funds possess a dark side, one that’s as insidious and harmful as the Sith in a Star Wars flick.

The cons of mutual funds are as varied as a big city jail cell, but the worst one by far is the fees.

Hold the Fees, Please!

All mutual funds charge fees. After all, the banks and institutions that offer these investment products are for-profit entities. And, to be fair, there are costs associated with operating a mutual fund, so it is only rational that those that benefit from the product (namely, the investors) bear the cost.

All mutual funds charge fees. After all, the banks and institutions that offer these investment products are for-profit entities. And, to be fair, there are costs associated with operating a mutual fund, so it is only rational that those that benefit from the product (namely, the investors) bear the cost.

The charging of fees isn’t the issue. It’s the amount of fees being levied that tips the scale into the egregious zone. Sadly, like much of the business world, Wall Street punishes you for your ignorance. They do reveal the fees in a fund’s prospectus. But the reality is few individuals get around to reading it and of those who do there is only a small subset who even understand what they’re reading.

Here are a few of the more common fees (unfortunately there are others!):

- Management fees

As the name suggests, these fees line the pockets of the fund’s portfolio manager

- 12b-1 fees

These fees are used to pay for marketing and advertising for the fund. You didn’t think an institution would be using their own money for this, did you? No! They use your dough to trumpet the virtues of their fund to bring even more money into their coffers.

- Redemption fees

Since mutual funds are designed to be buy-and-hold vehicles, many of them slap your hand if you sell your shares shortly after buying them. This punishment comes in the form of a redemption fee charged for selling anywhere from a few days to over a year after your purchase.

- Purchase fees

And speaking of purchase, some funds charge you when you buy shares. This is different than a sales load since it is paid to the fund and not the stockbroker.

- Sales load

If you’re buying a load fund, you will be charged a “sales load.” Think of this as a type of commission paid to the broker that sold you the fund. Sometimes these are paid at the time of purchase (i.e., front-end load), and sometimes they are paid at the time of sale (i.e., back-end load).

- Expense ratio

Sometimes called the total annual fund operating expenses, the expense ratio tells you the percentage of your investment that pays for the fund’s recurring fees every year.

Perhaps the easiest way to compare mutual fund fees is to zero in on the expense ratio. Simply put, the higher the expense ratio, the more money you have to pay every year for the privilege of owning the fund.

Suppose you own ABC fund and it has an expense ratio of 2%. That means if you have $10,000 invested in the fund you will be charged $200 each year. That may not sound like a lot, but if you assume the stock market only rises 5% that year, then 40% of your gain ($200/$500) gets eaten up in fees. Over decades that can add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost growth.

The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) has a helpful tool for comparing funds called the Fund Analyzer. With it, you can comprehensively analyze over 18,000 mutual funds to determine how the fees impact your performance over time.

A Better Mousetrap – ETFs

If all this talk of fees has your head spinning, worry not. The takeaway is simple – buying a mutual fund is the worst way you can go about investing in the financial markets. Fortunately, there is an alternative. One that boasts the same advantage as the mutual fund (namely, diversification), but improves on every single disadvantage.

If all this talk of fees has your head spinning, worry not. The takeaway is simple – buying a mutual fund is the worst way you can go about investing in the financial markets. Fortunately, there is an alternative. One that boasts the same advantage as the mutual fund (namely, diversification), but improves on every single disadvantage.

Truly, it is a better mousetrap.

We’re talking about the exchange-traded fund, or ETF for short. Like the mutual fund, an ETF is typically a basket of securities (like stocks or bonds) that investors can buy to achieve instant diversification. Unlike a mutual fund, however, the expense ratio of many ETFs is virtually nil. Down below we’ll compare the fees for both.

For obvious reasons, the ETF has exploded in popularity since bursting onto the public scene in 1993 – particularly over the past decade. These days ETFs track every single asset class from stocks and bonds to real estate, currencies, and commodities. You can even buy an ETF that provides exposure to a single country like China or something more exotic like mortgage-backed securities.

The following are things you CAN do with an ETF that aren’t possible with a mutual fund.

- Track the price and trade minute-to-minute (mutual funds are only priced once per day)

. - Buy on margin (that is, buy with borrowed money)

. - Sell short (allows you to profit when prices fall)

. - Trade options (opens the door to cash flow strategies like covered calls)

.

Given the myriad advantages that an ETF has, it’s a wonder why trillions of dollars are still parked in mutual funds. The reason why investors keep plowing money into these money stealing products is ignorance. That and the all too common situation where mutual funds are the only investment vehicles available in someone’s 401k.

.

A Fee-Focused Match-Up

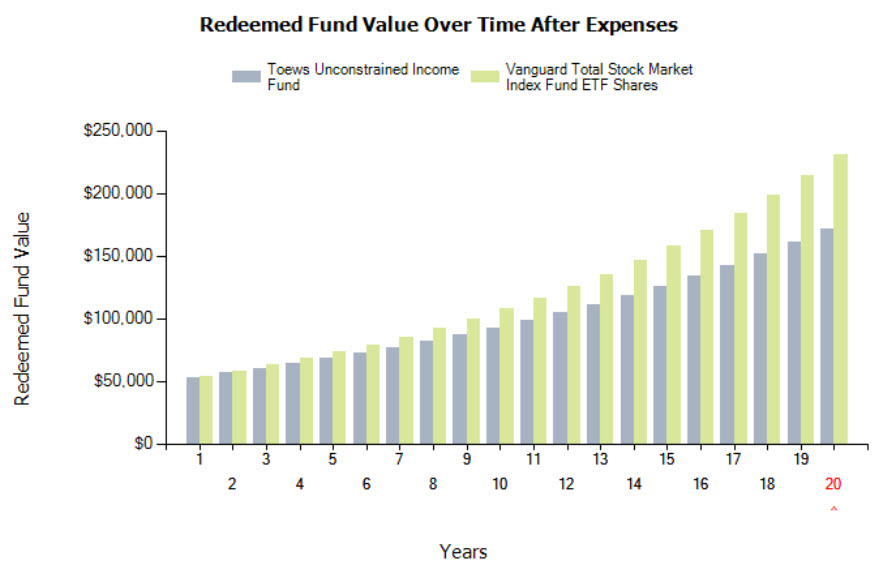

The best way to paint a picture of the detrimental, long-term impact of high fees is to show a side-by-side comparison of buying a higher fee mutual fund versus a low fee ETF. Instead of cherry-picking an insanely expensive fund, we’ll go with a run-of-the-mill fund that “only” charges 1.54%. For every $10,000 invested you’re paying $154 per year. Though it doesn’t sound like much, you’ll see how it can still rob you of tens of thousands of dollars. In case you’re curious the fund we used in the simulation is the Toews Unconstrained Income Fund (TUIFX). It was randomly selected.

For the ETF side we’re using one of the cheapest funds on the planet – the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTI) which has an expense ratio of 0.04%. For every $10,000 invested you’re paying a mere $4 per year.

For our simulation, we assumed we invested $50K in both funds and held for 20 years. The projected rate of return per year was 8%.

Over the first few years, the difference in fees appeared minimal. But look at how the gap grew over the back half of the data series! Are you ready for the details? Over two decades your $50,000 invested in the mutual fund rose to $171,274.89 producing an overall profit of $121,274. But here’s the kicker – you paid $30,337.91 in fees along the way! That 1.54% annual expense ratio doesn’t look so small anymore, does it?

In contrast, the $50,000 invested in the ETF grew to $231,191 producing an overall profit of $181,191. And the total fees you paid along the way? How about a scant $946.65!

ETFs are the clear winner and the vehicle of choice for the modern-day investor. Consider this your invitation to do further research on how to incorporate them into your investment plan.

Jill Milligan

Jill Milligan

December 7, 2017 at 4:39 PMMatt, Is this the newsletter that you were referring me to when we spoke last week? Is there also a video that I can share with my husband that perhaps explains ETFs vs Mutual Funds and not just about the fees?

FYI – we spoke about the Vanguard Mutual Funds that were referred to my husband from a friend of his.

Tim Justice

Tim Justice

December 22, 2017 at 3:46 PMThis is indeed that Newsletter….

As for Videos on the topic, I’m not sure what we have. Buzz an email to team@tackletrading and see if they can find you a resource for that.

Merry Christmas,